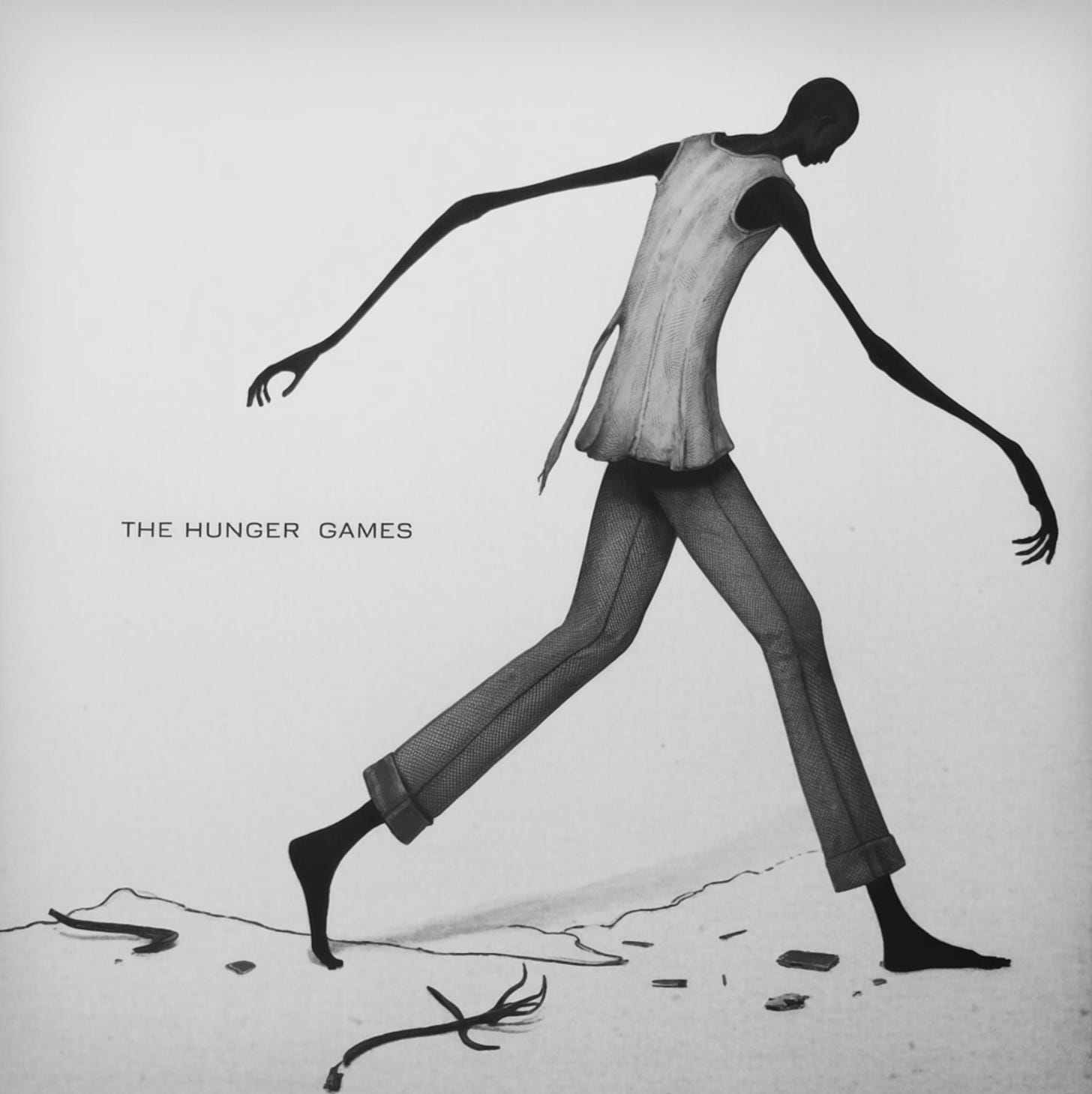

The Hunger Games

What two years on the fat jab has taught me about thinness, status, and the madness of the Ozempic scolds

This is And You’ll Be Okay Forever where I write about life, identity, society, storytelling, psychology, status, and other things. Please consider joining our community! Paid subscribers gain access to all weekly essays, the archive and community chat. Full subscribers additionally gain access to my popular ‘Science of Storytelling Live!’ online masterclasses, on fiction, non-fiction and technique. Recordings are made available for those who can’t make it on the night. The next masterclass, on technique, is on December 11th 18:00 UK time. Full subscribers also receive a personally dedicated, signed copy of my latest book.

Popular posts:

In Defence of Men: The rewards and sorrows of life as a success object

Three Stages of Being Childfree: Yes, no, but

A Crisis of Mattering: We feel alienated and dissatisfied because our world has grown too big

My new book, A STORY IS A DEAL, is available now

Here’s some momentous news that might have somehow escaped you: the bubbly British daytime TV presenter Alison Hammond recently had an unbubbly moment when asked by tabloid journalists about her “astonishing” weight loss. Hammond had somehow shed an enormous 85 kilograms and a reporter at the Women of the Year Awards in London wanted to know how. Did she do it through discipline, exercise and self-denial? Or did she actually use a fat jab? “Absolutely not,” she said, adding, “It worries me that the jab keeps getting brought up. Every single time I have a conversation in public, that is the question thrown at me.”

Hammond’s response was unsurprising, yet still curious. It was as if she’d been accused of some moral infraction. Why would it be worrying, these questions about the blockbuster fat-jabs Wegovy (aka Ozempic) and Mountjaro? These drugs are highly effective at tackling one of the most widespread, deadly and expensive conditions that afflicts our species. About one in every four adults and children in England are obese. The condition costs the NHS around £6.5 billion annually, is the second largest preventable cause of cancer, and is thought to be responsible for more than 30,000 deaths each year. Obesity will take around 9 years of life off the average person who suffers with it. These drugs – GLP1 receptor agonists – are the nearest we have to cures for the condition. Over the coming century, they might easily save the lives of millions. Why would being asked if you were using them be worrying? Is being asked if we took ibuprofen for our headache worrying? Do we fret that people might think, after breaking our leg, that we resorted to the use of a bandage?

It isn’t just celebrities who feel this way. One of our most famous high priests of dietary wellness, Professor Tim Spector – geneticist, microbiome expert and co-founder of the $250million personalised nutrition company Zoe – has said treating obesity with jabs is “horribly flawed” and “morally wrong”. The reason? Because if the drugs work, people will use them. “To deal with the problem of obesity and not the cause seems very reckless,” he said, “because you’re just producing more and more future customers of this weight-loss drug.”

Elsewhere, despite acknowledging the “incredible” efficacy of the drugs, Cambridge geneticist Professor Tom Yeo has argued they shouldn’t be used as a cure. “Prevention of obesity will require – will require – government policy changes, the hard miles, and I do fear, and this is a true fear, that actually not only our government, but many governments and policymakers, may very well use [these drugs] as a cop-out not to make the hard policy decisions.”

Meanwhile, over at The Guardian, writer Rachel Pick – who managed to lose 25kgs through diet and exercise – found “the explosive entrance of Ozempic into the cultural mainstream galling… The Ozempic moment neatly lays bare exactly how much our society still hates fatness and fat people, and the extreme measures people who are already physically healthy are willing to put themselves through to be just that much leaner.” Would she try the drug? She would not. “I would rather just stay fat than take a drug that completely rewires my most basic impulses.”

I’ve been using Wegovy (aka Ozempic) for more than two years. In the unlikely event that I’m able to keep affording it (my private prescription costs £300 a month) I intend to keep taking it for the rest of my life. After a childhood and adolescence of ribby weediness, I started putting on weight around my middle in my early twenties. I still remember the momentous day that I found a whole new way to hate myself. I was sat in an office on in industrial estate in St Mary Cray feeling repulsed, not just by the visual unappeal of the new sludge of flesh that was spilling over my waistband, but by what it said about me. Life is a battle of wills. The world roils with evil temptations and we’re stuck inside our heads, constantly making free choices to either fight the temptations or fold. Good people – successful people, worthy people, the kind of people you see getting kissed by curly-haired girls in Hollywood films – are the ones who choose against temptation, again and again and again. Good people fight off the devils that assail them. Bad people fail. They drink too much corner shop wine and eat too much Fruit n’ Nut. They’re like babies who can’t control their basic urges and I was like that, and you could see I was like that because of my fat, and, also because of my fat, everyone could see I was like that. That was how fat worked. It was a signal to the tribe, a physical confession you wore everywhere you went; a warning to the many about your sin and your weakness.